Projects, Mardi Gras - History

Historic Context of the Mardi Gras Shipwreck

The Mardi Gras Shipwreck falls within a critical time period for the historical development of the Gulf of Mexico region. At present, little is known about the site and its history. Aside from video data, the site has revealed few clues as to the vessel's age, function, and cultural affiliation. To date, two creamware artifacts have been recovered suggesting a possible date range of 1780 to 1820. Another prominent feature of the site is a ship's stove. Recent research suggests that this stove may represent a Brodie Patent Stove; Alexander Brodie began to patent his stoves around 1780 (Watson 1968:409). With this data, it is possible to begin to understand the historical circumstances surrounding the sinking of this vessel. Given what is known at this time, the following passages represent a general history of the Gulf of Mexico region at the time that this vessel met its demise. This historical assessment, while non-exhaustive, will provide context and augment the archaeological investigations that are proposed.

1750-1776

The historical significance of the Mardi Gras Shipwreck cannot be overestimated considering the overall importance of the region since the middle of the 18th century and its continued importance today. Indeed, the Gulf of Mexico was the scene of intense competition in North America beginning with Spanish exploration and continuing throughout the 18th and into the early 19th century. This competition expanded in the mid-18th century with the French and Indian War (usually referred to as the Seven Years' War in Europe 1753/4-1763). The war and subsequent peace (Peace of Paris) set the stage for a geopolitical struggle to control access to the region and availability to its natural resources (Chávez 2002:2). While the French and Indian War ended in 1763, conflict, which permeated the historic fabric of the region since 1750, continues even today as various oil and gas companies negotiate agreements in boardrooms across the region for access to valuable mineral resources on vast tracts of submerged lands throughout the Gulf of Mexico.

Figure 1. Treaty of Paris, 1763. Image courtesy of the United States Library of Congress.

During the mid-18th century, the power shifts determined in European courts were played out along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico in terms of human lives. A flood of colonists infused mixtures of various European populations among the Native Americans. An example is the mass deportation of Acadians to French Louisiana during the early days of the French and Indian War. Failing to adhere to the ideal of the "British imperial community" consisting of loyalty to the king and some form of Protestantism, several thousand French-speaking refugees from the region of Acadia (now Nova Scotia, Canada) were forced out and made their way to the Gulf Coast and into Louisiana (Anderson 2005:86-87). Ultimately, these people settled largely in the southwestern Louisiana region now called Acadiana; their descendants came to be called Cajuns.

The end of the French and Indian War resulted in France giving up all of New France (Canada) and all claims to the territory east of the Mississippi River to Britain. Spain, a weak ally to the French during the conflict, ceded Florida to the British. As compensation for Spain's loss, France in turn ceded control of the City of New Orleans and the remainder of French Louisiana to Spain (Anderson 2005:228-229). The most important concession, however, was the port of New Orleans and control of the Mississippi River, the artery to the interior of the North American continent. French administrative presence in North America was almost completely removed and the Aboriginal people of North America were decimated, pacified, or moved farther west. In addition, the British colonies and the American eastern seaboard began to assert their political and economic independence in the face of British demands for taxable revenue. A short 13 years later, the colonists would take up arms against the empire they once supported.

1776-1800

With the American declaration of independence in 1776, European Kings, such as the Spanish Bourbon king, Carlos III, and France's Louis XVI, saw an opportunity to aid the newly formed United States in their fight with an old nemesis, England. France entered the war in 1778 supplying troops, ships, and weapons to the cause, mainly to the northeastern colonies. While the war raged in the northeast, the Gulf of Mexico became its own theater of operations.

On June 21, 1779, Carlos III declared war against Great Britain and commissioned Louisiana Governor Bernardo de Gálvez to organize military (both land and naval) operations against the English (Chávez 2002:133-134). Gálvez focused attention on the British-held Gulf Coast, east of the Mississippi River. With aid from Spanish-held provinces such as Texas, Gálvez was provided with over 10,000 cattle for food and several hundred horses for his soldiers (Caughey 1972:136-138). In the summer of 1779, Gálvez led 1,400 men and captured British forts at Baton Rouge, Natchez, and Manchac (Davis 1971:111, 113-114; Caughey 1972:152-162; Chávez 2002:169-171). Gálvez's troops consisted of free Blacks, Creoles, and American Indians, as well as his own Spanish forces. On March 14, 1780, a month-long campaign ended against the British, and the 2,000 soldiers under Gálvez captured Fort Charlotte in Mobile, Alabama (Davis 1971:115-116; Caughey 1972:182; Chávez 2002:175-176).

Figure 2. Bernardo de Gálvez. Image courtesy of the Sons of the American Revolution.

In 1781, General Gálvez invaded the British provincial capital of West Florida, landing 7,000 men in Pensacola (Davis 1971:116-118; Caughey 1972:211; Chávez 2002:194). At Pensacola, Gálvez laid siege to the beleaguered fortifications and, after blowing up the powder magazine, the fort's commander capitulated and the whole of West Florida and 800 prisoners fell to Gálvez (Bunner 1842:152). The following year, Gálvez captured New Providence and the Bahamas. As he was preparing to invade Jamaica, negotiations brought an end to the war. Gálvez helped to draw up the final treaty and was acknowledged by the new American Congress for his assistance in the peace process. Recognition also came from the King of Spain for Gálvez's "… expulsion of the English from the entire Gulf of Mexico. Where they have so prejudiced my vassals and Royal interests in the times of both peace and of war" (Caughey 1972:213). It is possible that the Mardi Gras Shipwreck may represent one of the casualties of this conflict.

Figure 3. Gálvez's attack on Pensacola, 1781. Image courtesy of the Wikipedia

The end of the American Revolution in 1783 brought about change in the geopolitical landscape along the Gulf of Mexico Region. Spain regained control over Florida and the waterways that lead into the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. Spain also maintained a tight hold over Louisiana and the port of New Orleans. This peripheral colonial community, like many others throughout the history of the Spanish Borderlands, was vital to the Spanish Empire as the King and his administration feared that a compromise in territory along the Gulf of Mexico would result in the loss of valuable silver mines in Central Mexico (Faulk 1964:113; Hatcher 1976:69; Cruz 1988:56; Weddle 1992:100; de la Teja 1995:15).

1783-1803

Six years after the conclusion of the American Revolution, the Gulf of Mexico region continued as a focal point tied to events occurring throughout Europe. In 1789, the cacophony of revolution rang throughout European royal courts. The citizens of France, longing for independence from royal authority, rigid governmental structure, unrelenting absolute monarchy with feudal privileges for the aristocracy, and the Catholic clergy, took up arms with the cry of Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité (Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity). France underwent a radical change to governmental forms based around Enlightenment ideals of democracy, citizenship, and inalienable rights. These changes were accompanied by violent turmoil, including mass executions and repression during the Reign of Terror, as well as warfare with every other major European power. The results of these wars and shifting of territories spilled over into the Gulf of Mexico region.

As a colonial holding of the Spanish Crown, the Creole citizenry of New Orleans preserved some sense of loyalty to France. To quell this, Spain maintained a strong colonial administration over Louisiana, and its handling of economic conditions minimized the potential for revolution. Still, in 1793, Spain's control over the city of New Orleans was tested with the execution of Louis XVI and the declaration of war on Spain by France (Davis 1971:125). While these events were cause for concern, Spain continued its hold over the colony with only minor complications.

Another consequence of the French Revolution that impacted the Gulf of Mexico sprang from the French sugar colony of Santo Domingo (present-day Haiti). Beginning in 1791, slaves working in sugar plantations throughout the island took up arms and burned plantations. In 1803, after years of conflict and bloodshed, the republic of Haiti was born (Weber 1992:290). The result of this revolution was an influx of former French colonists and their slaves to Louisiana. This influx of Negro slaves was not new to Louisiana. As early as 1716, French Governor Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac imported slaves from Martinique, Guadeloupe, Santo Domingo, and other West Indies Islands to supplement the Indian slaves French colonists already used on their plantations (Davis 1971:50).

In 1800, France's new emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte, reacquired Louisiana from Spain as a condition of the Treaty of San Ildefonso (Weber 1992:290). The arrangement, which was kept secret for two years, was finalized with Spain in October 1802. As part of the agreement with Spain, France promised to keep the encroaching Americans from occupying Louisiana, providing protection for Spanish silver mines in Central Mexico (Weber 1992:290-291). Napoleon quickly violated the treaty and within a year sold Louisiana to the fledgling American nation. On April 30, 1803, upper and lower Louisiana, as well as the port of New Orleans, became an American Territory for the sum of $15 million dollars (Bunner 1842:175; Weber 1992:291). The push for American westward expansion was underway with Americans pouring into the region.

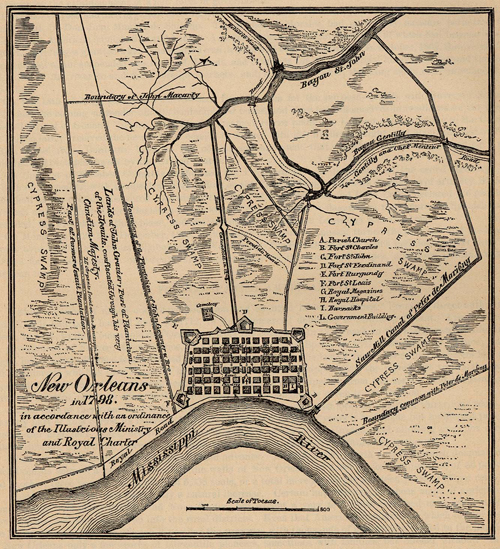

Figure 4. New Orleans, Louisiana in 1798; five years before the Louisiana Purchase. Image courtesy of the University of Texas Map Collection

Throughout the period, trade blossomed in the Gulf of Mexico region. One successful trade company was that of Panton, Leslie &Co. William Panton and John Leslie, both merchants from Scotland, immigrated to Georgia before the American Revolution. When the war began, these two Loyalists relocated to St. Augustine in British East Florida. Accompanying them were other Scotsmen, including Thomas Forbes, William Alexander, and Charles McLatchy. These individuals were experienced merchants who were heavily involved in the Indian trade. Working together, the men formed Panton, Leslie &Co. When Spain won title to both East and West Florida in 1783, the company was granted a monopoly to operate in the region (Davis 1971:136). The firm established several ports along rivers in West Florida and set up trade networks throughout the present-day southeastern United States. After Panton died in 1801, the Company was reorganized by John Forbes and continued in operation until around 1810.

Other forms of trade also existed in the region. In New Orleans, for example, trade focused on products shipped downriver to the local markets via riverboats that stopped at landings along the way. Many of these commodities were in the form of clothing, foodstuffs, shoes, and other items that also were exported to ports around the world, causing foreign trade to prosper as well. Mercantilist policies dominated Spanish-held Louisiana after 1763. These regulations were somewhat relaxed as time progressed and by 1782 direct trade with France and other ports of allied nations was permitted. Still, contraband trade with the British was prohibited, but continued, as Davis (1971:136) explains: "British vessels sailed directly to the mouth of the Mississippi and upriver past New Orleans, ostensibly on their way to the west Florida settlements of Manchac and Baton Rouge, but once past the city ‘made fast to a tree . . . where the people of the city and neighboring plantations came to trade with them.'" Indeed, smuggling served as the backdrop for the Gulf coastal economy and soon so would privateering.

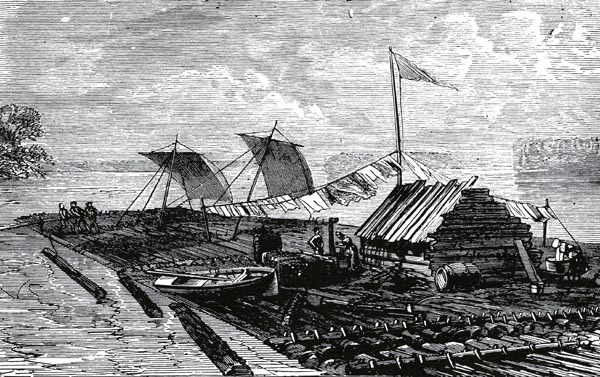

Figure 5. A raft on the Mississippi River, an important waterway for U.S. shipping and settlement westward, which ends in the Port of New Orleans. Image courtesy of the Mary and Washington College.

1803-1821

The period from 1803 to 1821 was a time of intensive expansion in the Gulf of Mexico region. Centered on the port town of New Orleans, the region saw pirates and patriots jostle for positions of power within New Orleans and, later, the barrier islands of the Gulf of Mexico. In addition, while privateering exploded as an occupation, the port of New Orleans grew as a commercial center. Upriver trade brought commodities such as cotton, flour, rope yarn, lead, whiskey, tobacco, pork, hides, and furs. European manufactured goods were imported and moved up the Mississippi River to markets in distant towns (Davis 1971:174). Coastal trade between New Orleans and British-held East and West Florida also grew (Clark 1970:322). Although trade was critical to the survival of New Orleans, the city did not achieve economic dominance as a commercial port until the middle of the 19th century. Clark's (1970) extensive treatment of the economic history of New Orleans suggests that during this time trade was extremely complex and fluctuated with global and regional economies, events, and politics. Still, as Thomas Jefferson pointed out, New Orleans was destined to become a "mighty mart of the merchandise brought from more than a thousand rivers" (Jefferson cited in Davis 1971:207). This prophecy was realized after 1820.

Anglo-American influence continued in the Gulf of Mexico region after the Louisiana Purchase. For example, Thomas Jefferson's former Vice President, Aaron Burr, hatched an ill-fated conspiracy either to invade Mexico and establish an independent republic or to convince the western territories of the United States to cede from the Union in an effort to set up a separate republic. Known as the "Burr Conspiracy," it is unclear to this day what exactly Burr intended to do. While Burr ultimately was acquitted of the charges against him, he was ruined professionally and financially. Furthermore, this aggressive move only confirmed fears that Americans had set their sights on the remaining portions of Spanish-held provinces such as Texas and Mexico (Davis 1971:172; Taylor 1984:49).

While Burr conspired to gain territory, Spain continued to maintain Florida as part of its colonial holdings. Anglo-American settlement had continued after the Treaty of Paris in 1763. Swearing allegiance to the Spanish Crown, these settlers secretly hoped that the United States would annex the territory. After the Louisiana Purchase, however, the ability to govern these settlers had become increasingly difficult. In 1810, contempt for the Spanish Government reached its zenith as a group of Anglo-American settlers revolted against the Crown and established the Republic of West Florida. This dispute continued into the spring of 1812 when the United States made Louisiana the 18th state and incorporated the Republic of West Florida as a series of parishes.

Growing tensions during the first years of the 19th century also led to a major conflict between Great Britain and the United States in 1812. The impetus for this conflict arose out of Great Britain stopping American merchantmen on the high seas and impressing American sailors into the Royal Navy, maintaining military ports on American soil, blockading American ports, and inciting Native Americans to raid and destroy American settlements. In the Gulf of Mexico, between 1805 and 1812, the British Navy and privateers blockaded and patrolled the mouth of the Mississippi River, seizing prizes going to and from the port of New Orleans. According to Clark (1970:322), this had a huge impact on the local economy of New Orleans and Gulf of Mexico region. "British warships and privateers caused serious difficulties for the trade routed south from New Orleans. New Orleans merchants sending cargoes to and receiving cargoes from St. Dominique [sic], Cuba, Vera Cruz, Campeachy [sic], and other colonial ports suffered severe losses from British seizures." These events, combined with British aggressions perpetrated along the eastern seaboard of the United States, culminated in Great Britain and the United States going to war. On December 24, 1814, after two years of fighting, diplomats from Great Britain and the United States came together at Ghent (present-day Belgium) to discuss terms and signed the Treaty of Ghent. This treaty was ratified by the Americans on February 16, 1815.

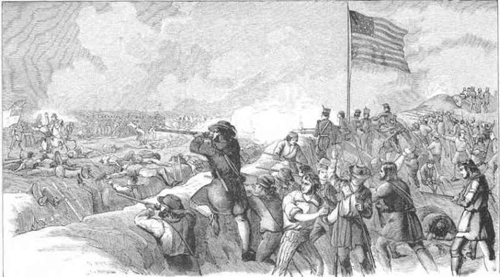

Back in the United States and unaware of the peace, General Andrew Jackson's forces, consisting of United States army troops; Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana militia; Baratarian pirates; Choctaw warriors; and free Black soldiers, moved into New Orleans in late 1814 to defend the city against a large-scale British invasion. On January 8, 1815, Jackson decisively defeated the British with more than 2,000 British casualties and fewer than 100 American losses. It was hailed as a great victory, making Andrew Jackson a national hero and elevating his popularity to such levels that he eventually won the presidency. After the battle, the British gave up on invading New Orleans and moved into position to attack the town of Mobile. However, when news of peace arrived on February 13, 1815, they sailed home.

Figure 6. Battle of New Orleans, January 8, 1814. Image courtesy of Project Gutenberg.

Another aspect of Gulf of Mexico history concerns the activities of pirates and privateers operating on the barrier islands that dot the Gulf Coast. Two infamous brothers, Pierre and Jean Laffite, maintained a large operation during this period. Between 1803 and 1804, the brothers moved to New Orleans and by 1808 were heavily involved in smuggling from the island fortress of Barataria to New Orleans. Essentially, the brothers held shares in many privateers that sailed throughout the Gulf of Mexico, as well as the Caribbean, bringing their prizes back to Barataria. A weak attempt by Governor William C. C. Claiborne to dismantle the pirates persisted throughout the years of 1808 to 1812 when the British fleet arrived to support the invasion of New Orleans. This invasion was the catalyst that Claiborne needed to break up the Barataria operation. Upon their arrival, the British asked Jean Laffite for aid. Laffite, in an effort to gain a pardon for his illegal activities and restoration of his confiscated goods, opted instead to fight on the side of the United States, supplying men, weapons, and his knowledge of the region. During the battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815, his followers helped the forces led by Andrew Jackson to secure an overwhelming victory. After the battle, Laffite and his brother attempted to regain the property they had lost at Barataria. However, in 1816, Laffite, unable to convince authorities that he deserved recognition for his participation in the battle, left for Galveston to establish the town of Campeche and resume privateering. Laffite became the master of Galveston, operating for a time with another pirate, Louis Michel Aury. Laffite's pirating operation drew the attention of the United States Government. Finally, confronted with the American Government's determination to end the Galveston establishment, the Laffites decided it was time to abandon Galveston early in May 1820. Jean Laffite sailed to Mugeres Island, off the coast of Yucatán, where he continued his illegal activities until around 1825.

Figure 7. Patriot/pirate, Jean Lafitte. Image courtesy of Encyclopedia Britannica.

The period between the admittance of the Gulf Coast States into the Union (Louisiana in 1812, Mississippi in 1817, Alabama in 1819, and Florida and Texas in 1845) and the Civil War was a commercial Golden Age for the Gulf of Mexico. An analysis of entries in the Ship Registers and Enrollments of New Orleans, Louisiana, between the years 1804 and 1820 indicates that most of this commerce was carried out aboard small ships frequenting Gulf ports to load cargoes that descended to the Gulf through the Mississippi River system. The Mardi Gras Shipwreck may represent an example of these small merchant ships. Excavation of the remains of this shipwreck should contribute to a more thorough understanding of the role of small craft and their cargo in the economic development of the American south and the dynamics of maritime trade in the Gulf of Mexico in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

References

Anderson, F. 2005. The War That Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War. Viking, New York.

Bunner, E. 1842. History of Louisiana: From its First Discovery and Settlement to the Present Time. Harper and Brothers, New York.

Caughey, J.W. 1972. Bernardo De Gálvez in Louisiana 1776-1783. Pelican Publishing Co., Gretna, Louisiana.

Chavez, T.E. 2002. Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Clark, J.G. 1970. New Orleans 1718-1812 An Economic History. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge.

Cruz, G. 1988. Let There Be Towns: Spanish Municipal Origins in the American Southwest, 1610-1810. Texas A&M University Press, College Station.

Davis, E.A. 1971. Louisiana A Narrative History. Third edition. Claitors, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

de la Teja, J. 1995. San Antonio de Béxar: A Community on New Spain's Northern Frontier. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Faulk, O.B. 1964. The Last Years of Spanish Texas 1778-1821. Moulton and Co., London.

Hatcher, A.A. 1976[1927]. The Opening of Texas to Foreign Settlement. Porcupine Press, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Taylor, J.G. 1984. Louisiana, A History. W.W. Norton & Co., New York.

Watson, W.N.B. 1968. Alexander Brodie and His Fire-Hearths for Ships. The Mariner's Mirror. 54(4):409-411.

Weber, D.J. 1992. The Spanish Frontier in North America. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

Weddle, R.S. 1992. Spanish Exploration of the Texas Coast, 1519-1900. Bulletin of the Texas Archaeology Society 63:99-122.